Engaging the Holocaust of Enslavement

We must carve out of the hard rock of reality the place we want to stand on and leave as a legacy for those who come after us–Maulana Karenga

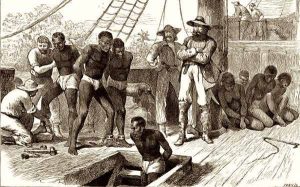

Enslaved Africans Transported

The struggle for reparations for the Holocaust of Enslavement of African people is clearly one of the most important struggles being waged in the world today. For it is about fundamental issues of human freedom, human justice and the value we place on human life in the past as well as in the present and future. It is a struggle which, of necessity, contributes to our regaining and refreshing our historical memory as a people remembering and raising up the rightful claims of our ancestors to lives of dignity and decency and to our reaffirming and securing the rights and capacity of their descendants to live free, full and meaningful lives in our times.

But this struggle, like all our struggles, begins with the need for a clear conception of what we want, how we define the issue and explain it to the world and what is to be done to achieve it. There are several ways to frame and approach this important issue or rather different aspects to one larger project:

(1) the legislative dimension as with the Conyers Bill, H.R. 40 and local and state bills and resolutions;

(2) the legal as N’COBRA and the Harvard group are doing;

(3) the political by which there is mass organization to support the project;

(4) the economic which is the major focus of all the above efforts; and

(5) the ethical initiative which I wish to engage in this paper. Our contention in the Organization Us is that the ethical dimension is the first and most fundamental dimension of the reparations issue and that unless that is engaged and successfully pursued, the issue of reparations will appear to lack moral grounding in the court of national and world opinion, and thus, will be cast as a claim unworthy of support on any other level.

In consideration of the issue of reparations as essentially and foremost an ethical issue, it must above all be framed in ethical terms. Therefore, the struggle for reparations begins with the definition of the horrendous injury to African people which demands repair. In other words, to talk of reparations is first to identify and define the injury, to say what it is and is not, to define its nature and its impact on the one(s) injured. Unless this is done first and maintained throughout the process, there is no case for reparations only an incoherent set of claims without basis in ethics or law.

This is why the established order works so hard to define away the historical and ongoing character of the injury. This is especially done in two basic ways. First, the injury is distorted and hidden under the category of “slave trade”. The category trade tends to sanitize the high level of violence and mass murder that was inflicted on African peoples and societies. If the categorization of the Holocaust of Enslavement can be reduced to the category of “trade” two things happen. First, it becomes more of a commercial issue and problem than a moral one. And secondly, since trade is the primary focus, the mass murder or genocide can be and often is conveniently understood and accepted a simply collateral damage of a commercial venture gone bad.

Holocaust popularized in the West

A second attempt of the established order to deny the horrendous nature of the injury and its essential responsibility for it is to claim collaboration of the victims in their own victimization. Here it is morally and factually important to make a distinction between collaborators among the people and the people themselves. Every people faced with conquest, oppression and destruction has had collaborators among them, but it is factually inaccurate and morally wrong and repulsive to indict a whole people for a holocaust which was imposed on them and was aided by collaborators. Every holocaust had collaborators: the Native Americans, Jews, Australoids, Armenians and Africans. No one morally sensitive claims Jews are responsible for their holocaust based on the evidence of Jewish collaborators. How then are Africans indicted for the collaborators among them?

Although there are other ways, the established order seeks to undermine the factual and moral basis of the African claim for reparations, these two are indispensable to its efforts. And thus, they must be raised up and rejected constantly, for they speak to the indispensable need to define the injury to African people and to maintain control of it.

As Us has maintained since the Sixties concerning European cultural hegemony, one of the greatest powers in the world is to be able to define reality and make others accept it even when it’s to their disadvantage. And it is this power to define the injury of holocaust as trade and self-victimization and make Africans accept it, that has dominated the discourse on enslavement in America. Our task it to reframe the discourse and initiate a new national dialog on this.

We have argued that the injury must be defined as holocaust. By holocaust we mean a morally monstrous act of genocide that is not only against the people themselves, but also a crime against humanity. The Holocaust of enslavement expresses itself in three basic ways: the morally monstrous destruction of human life, human culture and human possibility.

In terms of the destruction of human life, estimates run as high as ten to a hundred million persons killed individually and collectively in various brutal and vicious ways. The destruction of culture includes the destruction of centers, products and producers of culture: cities, towns, villages, libraries, great literatures (written and oral), and works of art and other cultural creations as well as the creative and skilled persons who produced them.

And finally, the morally monstrous destruction of human possibility involved redefining African humanity to the world, poisoning past, present and future relations with others who only know us through this stereotyping and thus damaging the truly human relations among peoples. It also involves lifting Africans out of their own history making them a footnote and forgotten casualty in European history and thus limiting and denying their ability to speak their own special cultural truth to the world and make their own unique contribution to the forward flow of human history.

It is here that the issue of stolen labor and ill-gotten gains which is seen as important to the legal case can be raised. For in removing us from our own history, enslaving us and brutally exploiting our labor, it limited and prevented us from building our own future and living the lives of dignity and decency which is our human right.

At this point, it is important to stress the role of intentionality in the Holocaust. Again, discussion of the Holocaust as a commercial project often leads to an understanding of the massive violence and mass murder as unintended collateral damage. Thus, to frame it rightfully as a moral issue rather than a commercial one, we must use terms of discourse which speak not only to the human costs, but to the element of intentionality. It is in this regard that Us maintains that maagamizi, the Swahili term for Holocaust, is more appropriate than its alternative category maafa. For maafa which means calamity, accident, ill luck, disaster, or damage does not indicate intentionality. It could be a natural disaster or a deadly highway accident. But maagamizi is derived from the verb -angamiza which means to cause destruction, to utterly destroy and thus carries with it a sense of intentionality. The “a” prefix suggests an amplified destruction and thus speaks to the massive nature of the Holocaust.

Clearly, it is issues like these and the ones discussed below which require an expanded communal, national and international dialog, which precedes and makes possible a final decision on the definition and meaning of the Holocaust, and the morally and legally compelling steps which must be taken to repair this horrendous past and ongoing injury. Therefore, in the context of holocaust, it is clear that reparations is more than receiving payments. Indeed, in the Husia, the sacred text of ancient Egypt, we find a concept of restoration, i.e., healing and repairing the world that is appropriate in discussing the reparations project. The word is serudj and it is part of a phrase serudj-ta, meaning to repair and heal the world making it more beautiful and beneficial than it was before. This is an ongoing moral obligation in the Kawaida (Maatian) ethical tradition and is expressed in the following terms: (1) to raise up that which is in ruins; (2) to repair that which is damaged; (3) to rejoin that which is severed; (4) to replenish that which is depleted; (5) to strengthen that which is weakened; (6) to set right that which is wrong; and (to make flourish that which is insecure and undeveloped. Again, then, an expansive and morally worthy concept of reparations as repair and healing requires more than monetary focus and payments.

Regardless of the eventual shape of the evolved discourse and policy on reparations, there are five essential aspects which must be addressed and included in any meaningful and moral approach to reparations. They are public admission, public apology, public recognition, compensation, and institutional preventive measures against the recurrence of holocaust and other similar forms of massive destruction of human life, human culture and human possibility.

First, there must be public admission of Holocaust committed against African people by the state and the people. This, of course, must be preceded by a public discussion or national conversation in which whites overcome their acute denial of the nature and extent of injuries inflicted on African people and concede that the most morally appropriate term for this utter destruction of human life, human culture and human possibility is holocaust.

Secondly, once there is public discussion and concession on the nature and extent of the injury, then there must be public apology. One of the reasons we rejected the one-sentence attempt to get a congressional apology is that it was premature and did not allow for discussion and admission of holocaust. In addition, as the injured party, Africans must initiate and maintain control of the definition and discussion of the injury. No one would suggest or contemplate Germans superceding Jewish initiatives and claims concerning their holocaust, nor Turks seizing the initiative in the resolution of the Armenian holocaust claims. The point here is that Africans must define the framework for the discussion and determine the content of the apology. And, of course, the apology can’t be for “slave trade,” or simply “slavery”; it must be an apology for committing holocaust. Moreover, the state must offer it on behalf of its white citizens. For the state is the crime partner with corporations in the initiation, conduct and sustaining of this destructive process. It maintained and supported the system of destruction with law, army, ideology and brutal suppression. Thus, it must offer the apology for holocaust committed.

Thirdly, public admission and public apology must be reinforced with public recognition through institutional establishment, monumental construction, educational instruction through the school and university system and the media directed toward teaching and preserving memory of the horror and meaning of the Holocaust of enslavement, not only for Africans and this country, but also for humanity as a whole.

Here it is important to note that the first holocaust memorial should have been for Native Americans who suffered the first holocaust in this hemisphere. And we must address their holocaust concerns and claims, as a matter of principle and with the understanding that until and unless they receive justice in their rightful claims, the country can never call itself a free, just or good society.

Fourthly, reparations also requires compensation in various forms. Compensation can never be simply money payoffs either individually or collectively. Nor should the movement for reparations be reduced to simply a quest for compensation without addressing the other four aspects. Indeed, compensation itself is a multidimensional demand and option and may involve not only money, but land, free health care, housing, free education from grade school through college, etc. But whether we choose one or all, we must have a communal discussion of it and then make the choice. Moreover, compensation as an issue is not simply compensation for lost labor, but for the comprehensive injury – the brutal destruction of human lives, human cultures and human possibilities.

Finally, reparations requires that in the midst of our national conversation, we must discuss and commit ourselves to continue the struggle to establish measures to prevent the occurrence of such massive destruction of human life, human culture and human possibility. This means that we must see and approach the reparations struggle as part and parcel of our overall struggle for freedom, justice, equality and power in and over our destiny and daily lives.

In the final analysis, this requires the bringing into being a just and good society and the creation of a context for maximum human freedom and human flourishing. Indeed, it is only in such a context that we can truly begin to repair and heal ourselves, our injuries, return fully to our own history, live free, full, meaningful and productive lives and bring into being the good world we all want and deserve to live in.

Copyright 2001 Dr. Maulana Karenga