Examples of Cultural Initiation Rites

See also | African Culture and Rites of Passage

Rites of passage play a central role in African socialization, demarking the different stages in an individual’s development (gender and otherwise), as well as that person’s relationship and role to the broader community. The major stage in African life is the transition from child to adult when they become fully institutionalized to the ethics of the group’s culture. Rites of passage are for this reason critical in nation building and identity formation. (Shahadah)

Don’t tear down a fence until you know why it was put up–African Proverb

AKAN

In Akan society, names are determined by the day on which the birth occurs. The Akan naming ceremony is known as Den to. Until the time for Den to has come, a baby is to remain in seclusion. Each day of the week is governed by a particular Obosom (divinity created by God). Therefore, the day on which the child is born is of great importance because the spiritual attributes of the Obosom of that day are transferred to the kra (or soul) of the child. Everyone receives a soul name that is known as kraden (plural: akraden) and that is again determined by the day on which he or she was born. Thus, a male born on a Sunday will be named Kwesi, Kwasi, or Akwasi, whereas a female will be named Akosua, Akousia, or Esi, all after the Obosom Awusi or Asi, who is related to the sun, and associated with leadership. In addition to their kraden, the child receives other names, in particular, their formal name, known as den pa, which identifies the child’s function and potential as it relates to his or her clan. The naming ceremony starts early in the morning of the eighth day. Family members and the elders gather at the father’s house. Prayers are said, libations are poured, and spirits are invoked. Two ritual cups are used, one containing a strong alcoholic drink (nsa) and the other containing water.

An elder on the father’s side will announce the child’s names. Gifts are then presented to the newborn, whose names are shared with every member of the community. Everyone, in honor of the child, will drink from one of the cups where water and nsa have been mixed and start sharing a meal.

When it comes to elders, in the case of the Akan, an individual becomes an elder by first being selected by his or her matrikin. The process involves the pouring of a libation by the older members of the lineage for the candidate who will become the Ebusua pinyin (head of the lineage). The elder, once chosen, joins other lineage heads and officials to sit on a council advisory to the ohene (king). Elders are referred to as nana. It is important to note, however, that not everyone who bears the title of nana is an elder, but every elder is a nana. When Akan elders meet, prayers in the form of libations are almost invariably said before any proceedings take place. It is believed that whenever two or more elders convene (such an occurrence is referred to as Nananom mpanyifo), the ancestors (abosom) are present. The person conducting the libation asks for the ancestors’ continued blessings and for protection, prosperity, and happiness for the entire community. The ancestors are offered the reasons for which the meeting has been called and request success for the endeavor.

In Akan culture, in order to become an ancestor, special ritual preparations are made by the maternal lineage of the deceased to facilitate passing of the spiritual personality. First and foremost, however to become an ancestor one must have been an elder. Ancestors are, therefore, separate and distinct from other spirits who are endowed with immortality. Becoming an ancestor requires that one live one’s life from the beginning in anticipation of the end. Eternal existence becomes possible after one has first achieved perception as an elder. As ancestors, elders have achieved the highest state of existence. They exist with God, but unlike God, they cannot create or the created order. Ancestors are dynamic. They can reincarnate via their spirits to help people.

It takes a village to raise a child– African Proverb

Maasai

Maasai girls from Kenya attend the Eunoto ceremony

Among the Masai, the Eunoto ceremony, which lasts for a whole week, is the rite of passage that marks the transition from childhood into adulthood for the males. It is an elaborate ceremony that marks the end of a relatively carefree life and the beginning of greater responsibilities. The initiates are then expected to watch over the community’s cattle (which are highly regarded as God’s unique gift to the Masai), participate in cattle raids, and kill a lion with their bare hands. At the end of the Eunoto ceremony, the young man’s hair is shaved, thus formally indicating the passage to manhood. In addition to having their hair shaved, they also have their skin painted with ochre in preparation for marriage. They then marry and start families.

Among the Masai of Kenya, circumcision is regarded highly as a mark of distinction and a symbol of valor and/or manhood and there are specific periods during which the circumcision rite is performed. Boys must prove themselves ready by performing certain manly tasks, including attending to cattle before they can be circumcised. When the boys feel they are ready, they approach junior elders and ask them to open a new circumcision period. For the Masai, circumcision determines the role a boy will play throughout his life, as a leader or a follower. A boy who cries out during the procedure is branded a coward and shunned for a long time and his mother is disgraced, whereas a boy who is brave and who has led an exemplary life becomes the leader of his age group. It takes months of work to prepare for circumcision ceremonies among the Masai, so the exact date of such an event is rarely known until the last minute. Both male and female circumcision have cultural and religious significance in some African societies. For example, if the request for a new circumcision period is approved, the Masai boys begin a series of rituals, including the Alamal Lenkapaata, preparation for circumcision or the last step before the formal initiation. Before Masai boys are circumcised, they must have a liabon, a leader with the power to predict the future, guide them in their decisions. The boys decorate themselves with chalky paint and spend the night out in the open. The elders sing, celebrate and dance throughout the night to honor the boys. It is worthwhile to note that, once a circumcision period ends, it may not be opened again for many years. The circumcision rite is taken seriously in African culture and religion.

Zulu

AFRICAN PEOPLE | AFRICAN CULTURE | AFRICAN MARRIAGE

Among the Zulu, birth, puberty, marriage, and death are all celebrated and marked by the slaughter of sacrificial animals to ancestors. Birth and puberty are particularly celebrated. To Zulu traditionalists, childlessness and giving birth to girls only are the greatest of all misfortunes. No marriage is permanent until a child, especially a boy, is born. The puberty ceremony (umemulo) is a transition to full adulthood.

Today, it is performed only for girls. It involves separation from other people for a period to mark the changing status from youth to adulthood. This is followed by “reincorporation,” characterized by ritual killing of animals, dancing, and feasting. After the ceremony, the girl is declared ready for marriage. The courting days then begin. The girl may take the first step by sending a “love letter” to a young man who appeals to her. Zulu love letters are made of beads. Different colors have different meanings, and certain combinations carry particular messages.

Dating occurs when a young man visits or writes a letter to a woman telling her how much he loves her. Once a woman decides that she loves this man, she can tell him so. It is only after they have both agreed that they love each other that they may be seen together in public. Parents should become aware of the relationship only when the man informs them that he wants to marry their daughter.

Among the Zulu people, a woman’s purity is sacred and reason for celebration. Every September, over twenty thousand Zulu virgins gather at the Zulu King’s Enyokeni Traditional Residence for the Zulu Reed Dance, a very colourful and meaningful ceremony. Traditionally, females gathered at the Reed Ceremony (Umkhosi woMhlanga) and men at the First Fruits Ceremony (Umkhosiwokweshwama). Female regiments during the reign of early kings were classified in age groups. The Zulu Reed dance is an educational experience and opportunity for young maidens to learn how to behave in front of the King. This is done while delivering reed sticks and dancing. Maidens learn and understand the songs while the young princesses lead the virgins. Traditional attire includes beadwork to symbolize African beauty at its best. At this stage the maidens are taught by senior females how to behave themselves and be proud of their virginity and naked bodies. That allows maidens to expect respect from their suitors who intend approaching them during the ceremony.

The second phase is educating the young maidens ‘amatshitshi’ by their older sisters ‘amaqhikiza’ on how to behave in married life. Young maidens are encouraged not to argue or respond immediately but to wish the suitor well on his journey back. After protracted discussions the older sisters then approach the mother of the impressed maiden about the impending love relationship. If the father accepts the suitor the two families meet and gifts are exchanged as a sign of a cordial relationship. After this the young maiden ‘itshitshi’ takes the next step of being ‘iqhikiza’ a lady in charge of the young maidens. By then they are experienced chief maidens who act as advisors to the younger maidens—and are ready for married life. The Zulu Reed Dance plays a significant part of Zulu heritage in reflecting diverse African customs. This ceremony is still close to the heart of many traditional leaders and citizens. It portrays and instills a sense of pride, belonging and identity among the youth. This ceremony has been tirelessly celebrated by countless generations in early September. Thousands of maidens converge on King Zwelithini kaBhekizulu’s palace to dance to the delight of the King, loyal subjects and guests. Only virgins are permitted to take part in this ritual. Each maiden is to carry a stick from the river and present it to the King in a spectacular procession at the Enyokeni Palace. The girls converge in groups from the Zululand regions to the Kings Palace the day before the ceremony. The activity promotes purity among the virgin girls and respect for women. The Zulu Reed Dance ceremony is the key element of keeping young girls virgins until they are ready to get married. The day of the ceremony the girls start walking to the main hut of the King. As the King appears to watch the procession of girls he is praised by his poets or praise singers (isimbongi). The girls collect a reed from a huge pile and proceed in a very long procession. They are led by the senior princess. As they pass the King they put their reed down and go back. While this is happening the men sing their songs and engage in mock fighting. After the festivities the King delivers a speech. This speech is a very direct and forthright message on the expected mores and traditions of the nation. The King is very direct and nothing is left to the imagination. He is a great proponent of celibacy until marriage. Afterwards, the maidens (over 20, 000 of them) join in unison ululating and singing the Kings praises in a joyous mood. As a cultural gesture, the group of maidens then get a name from the King to distinguish themselves from other women.

The Zulu people of Africa always burns the property of the dead to prevent evil spirits from remaining in the person’s home.

Mursi

AFRICAN PEOPLE | AFRICAN CULTURE | AFRICAN MARRIAGE

Once the initial cut is healed, it is replaced with a larger peg and as stretching takes place is replaced with increasingly larger pegs. Once the hole is large enough, the first clay or wooden plate (approx 4 cm across) is inserted. Over a year, plates become progressively larger. Women choose how far to stretch, but final plates can measure from 8 to more than 20 centimeters with some lower teeth being removed to accommodate them. It is traditional for only Mursi men to make wooden plates to be worn by unmarried women about 6-12 months prior to being ready for marriage. (The plates also distinguish the women from neighboring community women).When a Mursi girl has reached puberty and to mark the change of identity from girl to woman, she becomes a bansanai. To mark t his change, teens begin the process of stretching their lower lip. (similar to in process to ear stretching so prevalent in western culture today). They do this by cutting a centimeter long incision in heir lower lip and plugging it with a wooden peg.

his change, teens begin the process of stretching their lower lip. (similar to in process to ear stretching so prevalent in western culture today). They do this by cutting a centimeter long incision in heir lower lip and plugging it with a wooden peg.

The plates are not necessary to be worn at all times, and it is not uncommon to see women without them, however unmarried girls wear them in public and those that don’t are considered lazy or someone who does things in a hasty or clumsy manner and her bride price may be considerably lower. Wearing a lip plate defines a woman as mature, fertile and ready for marriage. Once married, the plates remind her of her ties to her culture and her husband. If her husband dies, the plate must be thrown away. Even if a woman is taken in by one of her deceased husband’s brother’s, it is unlikely that she will wear a lip-plate unless she is very young and without children. Similarly, if a close relative dies, such as a brother, a woman will not wear her lip-plate for many months or until her friends go to her to discuss and talk about the death and tell her that it is time that she stop mourning. Only when her friends invite her to the donga can she adorn herself again. Today, the Mursi battle a dilemma as young girls are beginning to choose not to stretch. This is viewed distastefully and may make it difficult to find a Mursi husband. The Mursi woman who does not have a stretched lip is said to be one who will rush to set down her husband’s garchu (basket used for carrying sorghum porridge), or kedem (gourd with either coffee, sour milk, or boiled leaves) because she feels uncomfortable and self-conscious around men. In short, she lacks the grace associated with womanhood, namely to be calm, quiet, hard working, and above all, proud.

Yoruba

AFRICAN PEOPLE | AFRICAN CULTURE | AFRICAN MARRIAGE

When a child is born among the Yoruba people, a special ceremony called The First Step Into the World is performed 3 days after birth. The purpose of this ceremony is to determine with the assistance of a babalawo (a priest of Ifa) what sort of person the child will be and to appoint an orisha (divinity) or guardian spirit. Once the father of the child has acknowledged it, the babalawo is consulted to determine which of the orishas will be the child’s protector, as well as what is forbidden or taboo to the child. The naming ceremony, called I-komo-jade, a child’s first outing or “outdooring” is performed on the seventh day after the birth for girls and on the ninth day for boys. A babalawo performs a purification ceremony called the Iwenumo, which is preceded by sacrifices offered to the deity who protects the child. During the Iwenumo, the babalawo throws consecrated water on the roof of the dwelling. The mother with the child in her arms runs out of the dwelling three times to catch the water falling from the roof. As she does this, the babalawo pronounces the name of the child. A fire that has been lit inside the house is ceremonially extinguished, and the ashes from it are carried outside. Following this, the members of the family give various names to the child while offering it gifts and best wishes.

Among the Yoruba people, during the marriage ceremony, the oldest woman in attendance will spray gin (which is closely associated with the ancestors) on the couple and other relatives to bless the new union.

In the Yoruba tradition, the distinction between an older person and an Elder reflects a significant shift in personal and collective responsibilities. Generally, it is the responsibility of adult men to protect and defend the community, whereas the adult woman’s responsibility is to nurture and educate the community. Accordingly, adult men are often consumed with the purpose and task of obtaining and providing those resources that sustain and advance life for themselves and their families. Likewise, adult women’s time and interests are devoted to securing and establishing an environment or area that is conducive to the growth and development of life for them and their families. The symbol of eldership for the Yoruba is the Onile, which is represented by two iron figurine spikes (one male, one female) joined at the head with a chain. The Yoruba believe that the head is the site of the spiritual essence of a person. The Onile symbolizes the sacred bond shared between the male and female elders and the importance of “the couple”. The emphasis on sexual attributes of the Onile is designed to convey the mystical power of procreation and the omnipotence of the Elders. The importance of the complementary nature that exists between men and women is similarly reinforced by the Ogboni Society’s unique gesture of placing the left (feminine) fist on top of the right (masculine) fist, with the thumbs concealed, in front of the stomach. This gesture represents both a sign of giving blessings as well as the recognition of the dominance of spiritual, sacred matters–and the primacy of the spiritual over the material. When men enter the community of Elders, they take on the role of Baba Agba, which means “senior father” or, more correctly, “nurturing father”. When women enter the community of Elders, they take on the role of Iya Agba, which means “senior mother” or “warrior mother”. It is the Iya Agba who plays the primary role as the spiritual protectors of the community. With the status of Eldership, women are devoted to protecting and defending (warrior mother) the spiritual balance of the community, whereas men are dedicated to securing and establishing (nurturing father) the spiritual harmony in the community. At the onset of Eldership, the balance and complementarities of the male and female principles are inviolate and always present.

Jola

The Jola, Dyola, Diola, or Yola (people) reside primarily on the Atlantic coast between the southern banks of the Gambia River, the Casamance region of Southern Senegal, and the northern part of Guinea-Bissau. Diola society has long been characterized by regional diversity. The ancient ritual of Bukut (boy’s initiation) takes place every 20-25 years for an entire generation of men between the ages of 12 and 35. Many men living abroad return to their local regions to participate in the ritual of Bukut. Like poro societies in West Africa, bukut takes place in the sacred forest. Elders and spiritual leaders teach the initiates ancestral secret knowledge as well as practical knowledge while secluded for a period of time in the sacred forest.

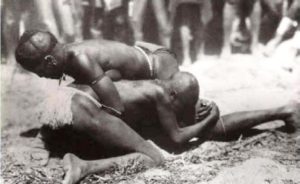

Jola wrestling Gambia

Bukut is a village (community) event that includes public celebrations such as singing, dancing, feasting, and shooting ancient trade muskets or homemade cannons; these acts of celebration are performed by those who have been initiated as well as by the neophytes. Women also play a major role in the initiation preparatory process on the village level; for example, mothers prepare food and compose songs for the neophytes, and the senior women in the compound greets the dancers at the ceremonial visit called the buyeet. In traditional thought, bukut is transformative; all males were regarded as children until they completed the bukut ritual, in fact, in Jola culture an uninitiated adult does not have the right to participate in consultations when important decisions must be taken for the greater good of the village or the community. The process gets underway with neophytes being cleansed in mystical baths prepared by Elders. After a performance of invulnerability by initiated men from the village, the initiates with shaved heads and bare torsos go into the sacred forest. Mothers, sisters and aunts accompany them to the edge of the forest. In the Jola cosmogony there are forces of good and forces of evil, the sacred wood tries to protect each Diola against the evil forces. Once in the sacred forest, secret rituals are performed, physical and mental tests are endured to harden them and to teach interpersonal skills such as loyalty, honor, work ethic and sense of solidarity. Circumcision is also practiced as a part of bukut. In ancient times this was performed in the sacred forest, though now many Jola are circumcised in hospitals/clinics. According to Abba Diatta, an Elder and former politician from the capital Ziguinchor, whose own initiation in 1951 lasted 3 months “This social organization prepares the initiates to become whole beings, ready to assume their responsibilities. We teach the young how to speak without speaking, how they must respect their parents and behave well with others.” When they emerge from the woods they will have lost their indolence and the irresponsibility of children and will be united as men appearing in a new style of dress. At the close of the ritual, the newly initiated men also adorn elaborate masks filled with symbolism as part of the ceremonial process.

Recently, at the urging of the younger generation who threatened to go elsewhere to be initiated, 16 villages revived initiation rites after not having them since 1968. The delay is attributed to the growth of Christianity and Islam. Out of respect for tradition, the simmering conflict in the Casamance between the army and separatist rebels which goes back to 1982 and has caused many deaths was momentarily forgotten.

*Sources: Encyclopedia of African Religion and blog post from Bantaba in Cyberspace

Sankofa

A return to basic ideals of what is tried and true in ancient as well as living African societies does not mean that we have to return to “living in grass huts and wearing loin cloth”. It is highly possible, indeed necessary, based on current states of being, to adapt these methods to the modern world and our current living situations, as a practical and systematic solution to current problems facing African youth and communities. Remembering who we are is the beginning; acting on that knowledge within our own spheres of reality is the logical next step in the circle of life.