Religion in the African Diaspora

Religion January 14, 2015 Kofi Asare Opoku

RELIGION THE DIASPORA

This page was created to foster understanding between diverse religious communities. Religious intolerance and bigotry are totally incompatible with a Pan-African future. And this generation will stamp it out.

Candomble religion in the African Diaspora

The core of religion in traditional Africa consists of a belief in a Supreme Being known by various names in the different languages in African societies. Especially, in the culture areas of Africa whose influences were to become prominent in the Americas, this Supreme Being goes by such names asOlorun and Olodumare, among the Yoruba; Mawu-Lisa, among the Fon of the Republic of Benin;Onyame and Onyankopon, among the Akan. This Supreme Being is the Creator (Chineke – the Spirit that creates, among the Igbo of Nigeria) and Sustainer (Mebee – the One who bears the World, among the Bulu of Cameroon), of the universe. There are no visual representations of the Supreme Being, who is understood to be a Great Spirit, as the Igbo name , Chuku (Chi – spirit; uku – great), makes e

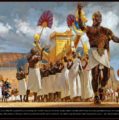

Salvador, Bahia, Brazil February 2nd is the feast of Yemnaja, a Candomble Umbanda religious celebration where thousands of adherents to these faith religions go to Rio Vermehlo Red River to make offerings of flowers and prayers, paying their respects to Yemanja, the Orixa goddess of the Sea and water

xplicitly clear. And because the Supreme Being is a Great Spirit, there are no temples built specifically for Him/Her, the Yoruba say: “Since Olorun is everywhere, it is foolish to try to confine him/her in a temple”. The Akan also say, “If you want to speak to Onyame, speak to the winds”. Like the winds, Onyame is invisible and is everywhere.

The Great Spirit has attendant spirits, children, agents or messengers who ran errands and who reflect aspects of the nature of the Great Spirit. The Yoruba call such beings Orishas, and clearly distinguish between them and Olorun. For the Yoruba, these Orishas are many, numbering 400 + 1 all the way up to 1600 + 1, leaving room for humans to discover the multifarious dimensions or manifestations of the power of Olorun. These Orishas include: Orisha-nla (the Yoruba arch-divinity, and Olodumare’s deputy,

who assisted in the creation of both the earth and human beings); Ogun, the Orisha of iron, who led the Orishas from the heavens into the world and cut a path through the thickets with his machete and thus had the title, Chief of all Deities, Osin-Imale, conferred on him by the Orishas.

Other Orishas are Orunmila, also known as Ifa, divinity of wisdom and divination and an omnilinguis, who understands every language spoken under the sun; Shopona or Obaluaye, the Orisha of smallpox and epidemics; Osanyin, the Orisha of herbal medicine and Olokun, the Orisha of the ocean.

In the Fon area of West Africa, Mawu, the female aspect of Divinity, represents the moon and symbolizes coolness, wisdom and mystery. Lisa, the male aspect of Divinity, represents the sun, heat, strength and energy. Similar to the Chinese yin and yan, these opposites, in their interaction, give rise to complementarity and this feminine-masculine interaction constitutes the very nature of the universe. The interaction between Mawu and Lisa is conceptualized in Fon religious thought as Da, the embodiment of force or power, and is represented by the serpent, which is the symbol of flowing, sinuous movement.

Below Mawu-Lisa are the Vodu, who are the offspring of the union between the twin divinity. The Vodu are associated with features of the environment and manifest themselves as Vodu of rivers, oceans, mountains, fire or as Vodu of natural phenomena, such as thunder and lightning and epidemics. The Vodu are in control of aspects of life and their devotees offer them sacrifices, prayers and libations in order to secure their protection. Among the Fon Vodu, are Gu, Vodu of iron and warfare, who made the world habitable; Fa, Vodu of divination; Sagbata , the Vodu of grains, agriculture and harvests; Legba, the Vodu of communication and entrances who opens the way for the other vodu. There is also Agoue or Agwe, the Vodu of the ocean.

A major component of the world-view has to do with belief in ancestors who, together with the Great Spirit, are always revered and are believed to continue to live after death and to be active in the lives of their relatives by punishing and rewarding them.

The world is populated by spirits which are able to possess humans, and the possessed persons become the mouthpieces of the spirits through whom the wishes of the spirits are made known. The world of spirits and the world of humans do not exist in isolation from each other, they interpenetrate, and the presence of the spirit in a person is evidence of the concern and care the spirits have for humans and the communication that takes place between them.

Religious life includes rites to mark the various stages in the cycle of life; healing practices by herbalists, medicine men and women; sacrifices; narration of sacred narratives, legends and folktales, dancing and singing. Spiritual practice includes movement which put humans in tune with the vital spiritual forces of the universe.

And lastly, the world view the Africans brought with them recognizes the existence of a power or force in the universe which could be tapped by those with the necessary expertise for beneficial or injurious purposes. The negative use of this force is what is called witchcraft and sorcery or Obeah, in the Caribbean Islands.

On the whole, the religious traditions the Africans brought with them to the Americas aimed at improving the lives of people during their passage through this world rather than a preparation for life in a future world that was yet to come.

Africans in the Americas:

In South America and the Caribbean, African cultural traditions became more prominent and obvious than they did in North America and the reasons are due to the numerical strength of the Africans and the duration of the slave trade. The importance of numbers helps to explain the existence of orthodox African belief systems in Candomble in Brazil, Santeria in Cuba and Vodou in Haiti.

In South America and the Caribbean, the Africans were able to continue their ethno-medical systems because they found similar plants with which they were familiar. The runaway slaves who established free communities and maintained African cultural traditions helped to retain much of their traditional culture. And in areas where the slave trade lasted longer, African religious values were reinforced as new shiploads of Africans were brought in.

In the Catholic countries, Black Brotherhoods were encouraged and in these brotherhoods the African descendants were free to perpetuate their ideas, customs and languages. Although in the Catholic countries, Africans were forcefully baptized into Catholicism and were forbidden to practice their own religions and customs, there was no forceful programme of indoctrination and the Africans therefore secretly held on to their beliefs of their ancestors in Africa, oftentimes under the guise of Catholicism.

Besides, the Catholicism which the Africans encountered had many correspondences with the religious traditions the Africans brought with them. The number of Catholic saints who solved the earthly problems for people corresponded to the Orishas who helped their devotees, and for the African descendants, the saint and the Orisha were the same. The elaborate Catholic rituals, feast days and processions also helped the African descendants to identify their religion with Catholicism. And while the African descendants maintained the fundamentals of their religious heritage, they could make many correspondences with Catholicism and disguise their religion as Catholic.

But above all, the strength and resilience of the African religious traditions and the determination of the African descendants to hold on tenaciously to them as their only firm ground upon which to base their resistance to a system that was bent on their death, culturally, religiously and otherwise, enabled the African descendants to survive and prosper in their new homelands.