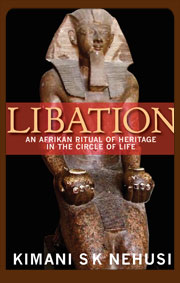

Libation | A Ritual in African Life

Culture May 8, 2013 Kimani Nehusi

A Ritual of Heritage in African Life

Pour libation for your father and mother who rest in the valley of the dead. God will witness your action and accept it. Do not forget to do this even when you are away from home. For as you do for your parents, your children will do for you also– Book of Ani (Kemet)

See Also | Religion in Africa | African Kingdoms | Rites of Passage | Traditional Healing

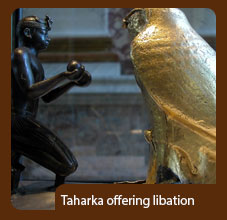

Libation in Africa is a ritual of heritage, a drink offering to honor and please the Creator, the lesser divinities, our sacred ancestors, humans present and not present, as well as the environment. This ritual is also practised in many other parts of the world. Among Africans it may also be deployed to issue curses upon wrongdoers.

The ritual achieves this objective by promoting and The ultimate purpose is to promote the cosmic order of oneness and balance of the beings and things in the universe. Safeguarding the correct relations among and between all the beings and things in existence. The origins of libation are so old that the first records of the ritual can be found in the legends, myths, sacred literature and language of Kemet (ancient Egypt).

But it is almost certain that this ritual existed even before then. Libation is found throughout the African world: on the continent as well as in the Americas, the Caribbean and other parts of the world where Africans dwell. The significance of this ritual transcends its distribution across the immense time/space correlation that is occupied by the African experience of life. Libation is an immensely important part of the African cultural equipment. In fact, this ritual is a marker of African identity. Its persistence across place and places, and time and times, says much about the origin of all Africans, about their relation to each other and about cultural transmission in general.

ORIGINS: Legend, myth and divinity

The origins of libation in Africa are to be found in the heroic, the legendary, the mythical and the divine in: Kmt: Kemet (ancient Egypt), well over 5000 years ago. Less is known about: KAs: Kas(h),later rendered:KAS: Kush, or about : Ta Seti, literally ‘Land of (those who carry the) Seti Bow’ or Nubia and other African states that preceded Kemet and gave it the fundamentals of its culture and indeed much more. But an incense burner found in the Nile Valley at Qustul, in lower Nubia, near to the current border with the Sudan and Egypt indicates both an anteriority of censing to Kemet and, by implication, also of the ritual behavioural complex to which censing belongs.

The origins of libation in Africa are to be found in the heroic, the legendary, the mythical and the divine in: Kmt: Kemet (ancient Egypt), well over 5000 years ago. Less is known about: KAs: Kas(h),later rendered:KAS: Kush, or about : Ta Seti, literally ‘Land of (those who carry the) Seti Bow’ or Nubia and other African states that preceded Kemet and gave it the fundamentals of its culture and indeed much more. But an incense burner found in the Nile Valley at Qustul, in lower Nubia, near to the current border with the Sudan and Egypt indicates both an anteriority of censing to Kemet and, by implication, also of the ritual behavioural complex to which censing belongs.

Libation belongs to this complex. It is suggested that libation originated somewhere in the upper Nile Valley, in central Africa, and was taken northwards down the valley and eventually to other parts of the continent by migrating Africans as part of their cultural equipment, something inseparable from themselves. If the significance attached above to the Qustul incense burner is tenable, then the libation complex must have made this journey along the Nile uncounted generations ago. Scholarship is on firmer ground from the time of Kemet; there is a mass of details about libation from very early in the history of this very ancient African country. But cultural influence, certainly in the case of libation, did not travel only in one direction along the Nile. There is evidence that particular styles of libation developed in Kemet later impacted back upon the ritual in places further up the Nile Valley, towards the source of both the river and this cultural practice. One example was uncovered at Meroe. Despite Eurocentric misrepresentations to the contrary, it is also certain that Kemetic style libation, as well as the very idea and practice of this ritual, were passed on to Alexandrian Egypt, Greece, Carthage and Italy (Delia, 1992, pp. 181-190), thus confirming more general conclusions about the transmission of knowledge and culture reached by Herodotus.[3]

The origins of the ritual of libation are so ancient and so important that even to the people of Kemet they were obscure, lost in the mists of time, and therefore accounted for in legend and myth. In one such account of things, the sun divinity Ra retreated in anger from humans and from the earth because of the latter’s irreverence in plotting against him and ridiculing him because he had grown so old that he drooled. He sent his daughter, Hathor, to avenge his hurt. She decided to wipe out humanity and proceeded so well that Ra changed his mind and wanted to stop the slaughter, but Hathor’s blood lust could not be easily arrested. Eventually she was stopped by a trick. Served copious quantities of red beer, she drank, believing it to be blood, and became so drunk that she forgot about killing. So humanity was saved. In Ayi Kwei Armah’s estimation, “[t]his legend explains the rise of a propitiatory custom found everywhere on the African continent: libation, the pouring of alcohol or other drinks as offerings to ancestors and divinities.” (Armah, 2006, p. 207).

Divinities are the central characters in the drama, which is a parable on the maintenance of the entire cosmos, not just humanity. Most of the action takes place in the realm of divinity, for in the African world view, it is ultimately here that power lies. Humanity is initially the active source of discord, but the human role very quickly becomes purely passive and is in fact outweighed by divine intervention, ultimately with libation to save the world.

The drink offering in this myth is literally as well as figuratively an exchange for the blood of humanity and the restoration and preservation of the cosmic order. The role of liquid offering is central in the ritual of libation, the ultimate meaning of which is the necessity for the restoration and maintenance of the cosmic order.

Sacred Literature

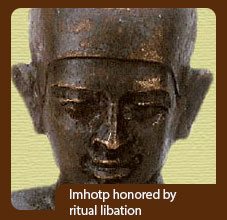

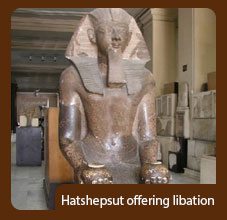

The origin of libation among the heroic, the legendary, the mythical, the magical and the divine is reflected and reinforced by its status in the sacred literature of the Classical African Tradition in Kemet (ancient Egypt), where it is an ancient command from the practice of the sacred African ancestors. An example of divine libation is that scribes in Kemet ritually poured libation in honor of Imhotep after he became an ancestor and then made divine. The regular performance of this ritual drama is therefore made mandatory upon all Africans.

The origin of libation among the heroic, the legendary, the mythical, the magical and the divine is reflected and reinforced by its status in the sacred literature of the Classical African Tradition in Kemet (ancient Egypt), where it is an ancient command from the practice of the sacred African ancestors. An example of divine libation is that scribes in Kemet ritually poured libation in honor of Imhotep after he became an ancestor and then made divine. The regular performance of this ritual drama is therefore made mandatory upon all Africans.

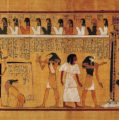

Libation is both ancient and important, evidence of this is found in the pyramid the oldest substantial writings in the world, and Utterance 598 in the Coffin Texts, the successor corpus, may well be a libation Utterance.In the Sfdw prt m Hrw: Book of Becoming Enlightened, popularly known in the west by the erroneous and misleading term ‘The Egyptian Book of the Dead’, the Sfdw prt m Ani: Book of Ani, commands us thus:

Pour libation for your father and mother who rest in the valley

of the dead. God will witness your action and accept it. Do not

forget to do this even when you are away from home. For

as you do for your parents, your children will do for you also.

(Karenga, 1984, p.53).

Language

Linguistically the words for libation in the:Medew Netjer, the language of Kemet that is popularly called hieroglyphs appear to have originated in two different terms. These two roots areor: cool through water and: ‘to humble oneself (before a divinity)’.(Erman and Grapow, Vol. V, 1982, p.22). It appears that over time these two different words with different meanings became fused into the single and composite concept of libation.

Linguistically the words for libation in the:Medew Netjer, the language of Kemet that is popularly called hieroglyphs appear to have originated in two different terms. These two roots areor: cool through water and: ‘to humble oneself (before a divinity)’.(Erman and Grapow, Vol. V, 1982, p.22). It appears that over time these two different words with different meanings became fused into the single and composite concept of libation.

But these terms by themselves, singly or collectively, do not cover the full meaning of the concept. The Wörterbuch contains an extensive listing of the cognates or related words. This list includes meanings such as to humble oneself before a divinity, cool, to be cool, the act of cooling oneself, and several meanings of cool which originate in the physical state produced by pouring cooling water over the body and extend themselves in a continuum ranging from this physical state to include mental,

emotional and spiritual conditions that are all related because they are all induced by and or are similar to the state created by this act of water pouring: to freshen up, comfortable, relaxed, speech that is careful (and therefore unexcited and non-threatening), to restore to health, satisfied (from ritual sacrifice), left in peace, happy state.(Erman and Grapow, 1982, Vol.V, pp. 22-31).

The central concept in almost all these meanings arises from the state of satisfaction and even pleasure that is born from the absence of discomfort induced by the cooling property of water. It is this basic meaning that is extended to embrace the many shades of meaning that arise in all of these words. Thus, aspects of the person (for example the mouth and other organs), places and even actions may be cool, be in a cool state or be done in a cool manner. This notion of ‘cool’ and the state of wellness it represents captures the meaning and objective of libation, which is to ensure the oneness of all the beings and things in the cosmos through the maintenance of this divine cosmic order, or Maat, a concept first articulated and encountered in Kemet. Interpretations vary. However, this concept may be translated roughly as truth, justice, righteousness, order, balance, harmony and reciprocity. Maat has been described as ‘the key idea in the traditional African approach to life’ which today ‘recurs in most African societies as the influence of right and righteousness, justice and harmony, balance, respect and human dignity.’(Asante and Abarray, 1996, p. 59). Notions of order and balance represent a deeper meaning of asé, the Yoruba word for the vital force that is also represented in kA in the Medew Netjer and muntu in the Bantu languages. Asé is therefore conceptually a continuation and restatement of Maat. The two – or maybe the two labels of the same thing – are also linked in practice, for libation is about maintaining Maat for the people of Kemet as it is about maintaining asé for the practitioners of the ways of the Orisas, of Voodoo, Shango, Kumina, Candomblé and Santeriá. For all Africans, libation is a path to the divine cosmic order; that is, the correct relations among people, other beings and things in the entire cosmos.

STRUCTURE AND SIGNIFICANCE

The libationer(s): the one(s) who perform(s) the ritual, enter(s) into this undertaking in order to recognise and proclaim the existence and superiority of those higher powers; to solicit and obtain their blessings for a particular individual or a particular group; to repair imbalance in a person, a family, a clan, a sub-group or in the African nation or in the physical environment, or to nullify the perceived threat of such imbalance; to obtain blessings for a project that is to be started, or for one that has already been started or has been completed; to issue a curse upon ill wishers or evil doers; or for any combination of these foregoing reasons, and usually to obtain general blessings and all other benefits – psychological, spiritual or otherwise – that arise from the recognition, acknowledgement and benevolence of those powers that are greater than us mere humans. The overall emphasis is upon maintaining the correct behaviour towards all beings and things in the cosmos, and therefore the correct relationships with them.

The libationer(s): the one(s) who perform(s) the ritual, enter(s) into this undertaking in order to recognise and proclaim the existence and superiority of those higher powers; to solicit and obtain their blessings for a particular individual or a particular group; to repair imbalance in a person, a family, a clan, a sub-group or in the African nation or in the physical environment, or to nullify the perceived threat of such imbalance; to obtain blessings for a project that is to be started, or for one that has already been started or has been completed; to issue a curse upon ill wishers or evil doers; or for any combination of these foregoing reasons, and usually to obtain general blessings and all other benefits – psychological, spiritual or otherwise – that arise from the recognition, acknowledgement and benevolence of those powers that are greater than us mere humans. The overall emphasis is upon maintaining the correct behaviour towards all beings and things in the cosmos, and therefore the correct relationships with them.

A libation may be poured with any drinkable liquid, including water, milk, wine, beer, or strong spirits (alcohol), though alcohol has been the dominant choice for some generations now, especially in West Africa and the West. More often than not clear spirits are chosen on important occasions: gin in Ghana, clairin in Haiti, white rum in Jamaica, Guyana, Trinidad, and other places. This predominant choice is almost certainly because of the physical resemblance between clear spirits and pure water, for the latter has always been regarded by Africans as the ultimate agent of both physical and spiritual purification. However, in more than an echo from Kemet, where “certain oblations [were] suited to particular gods, others inadmissible to their temples, and some more peculiarly adapted to prescribed periods of the year,” (Wilkinson, Vol. I, 1994, p. 263) certain contemporary African divinities may have their individual preferences about drink and food. For example, among the loa (divinities) of Voodoo in Haiti, the liquid of libation “varies according to the god. It is sweet liquor if it is Damballa, rum for Ogun, Loco or Legba.” (Hurston, 1990, pp.175 and 235). It is red wine or any home made wine or babash (Trinidad moonshine) for Shango in Trinidad. In Candomblé in Brasil, Oshun’s favourite food is Xinxin de galinha, that of Shango is maala or caruru, Obatala’s is white rice, abará vatapá, acarajé, etc. (do Nascimento, 1995, p. 57).

In African practice there is a sharp distinction between some things that are done with the right hand and other things that are to be done only with the left hand. Libation is poured with the right hand because this is the hand reserved by African tradition for such activity as offering, eating and drinking. A libation often accompanies offerings of food and other things considered good and worthy of the higher powers, but libation should not be confused with those other offerings or with entire ceremonies of which it may form a part. For example, from the earliest known times, libations are always poured as part of the rituals which mark the African cycle of life: Naming Ceremonies, Initiation Ceremonies, Marriage Ceremonies and Transition Ceremonies (funerals). Libation is also poured at other occasions, such as to mark the settlement of a dispute, before chopping down trees (individually or parts of a forest), at the Enstoolment of Chiefs, at the many festivals in the African calendar, at the opening of Voodoo, Shango, Candomblé and other African spiritual gatherings, and indeed in every ceremony and gathering in the African way of life. The general purpose is to safeguard or make amends and seek forgiveness for infracting any of the relationships in the cosmic order, but the specific occasions and themes in libation may be many, as is illustrated by Abu Abarry’s consideration of Ga libation oratory (Abarry, 1996, pp. 92-95) or in the Igbo invocations, or indeed in the libation practice of the many existing groups of Africans.

Purposes

If properly done, the person, the family, the clan, the community or the nation (i.e. those present and participating and or those on whose behalf the libation is poured) may receive several benefits from a libation. They may benefit through being fortified by the renewal and or restoration which this ritual offers. They may also receive benefit through the security that comes from the knowledge of the spiritual connection and oneness with the Supreme One, with the divinities, with the ancestors, among themselves singly and collectively, and with the physical environment. It is the preservation of these connections and the beneficial results of understanding and maintaining them that this ritual represents and promotes.

Buy African Clothes– Click Ocacia.com

Libation, like any activity that is at once both sacred and communal, is useful and important because it helps to overcome fears, anxieties and frustrations. It promotes knowledge of and respect for elders and the Ancestors, hope and healing, unity and harmony, all through the reinforcement of common bonds. It also lends itself towards the achievement of solidarity, which results from common participation in any such communal activity. Libation also functions beneficially by helping those present to be psychologically prepared for a task at hand, especially through the self-confidence that grows from the knowledge – not only that all is well in their relationships with the higher and lesser powers in the cosmic order, but also by becoming focused upon what is to be done during a specific forthcoming undertaking. This latter is normally achieved by rehearsing the proceedings in one’s mind before actually embarking upon the undertaking(s). In a similar way libation is also helpful because it empowers us to focus upon all the tasks and expected challenges in a particular venture or during a specific day – or indeed within any time period – that may be unfolding before us and which may be addressed in the libation Statement. In short, libation helps to create an enabling psychological climate for forthcoming action.

However, libation must not be a substitute for human labour or human struggle, as prayers are sometimes viewed.

A particular libation may be part of an occasion specifically devoted to the Supreme Being, or to a particular divinity, or to an Ancestor, or even to a living leader, but every part of African society is usually acknowledged in the statement accompanying the pouring, including families, clans and the entire collective.

In addition to the occasions mentioned above, libation is generally made at the beginning of the day, of a meal, or of a special ceremony to honour the Supreme Being, or a particular divinity, or an Ancestor. Libation may also be an important part of a ceremony arranged specifically to mark the commencement of an important piece of work (e.g. the building of a house), at the completion of a significant piece of work (the building of a house, or its cleansing or its dedication if these are not the same), or in recognition of an important achievement (success at exams, an earthday, the attainment of a certain stage in spiritual growth, the end of a period of struggle, recovery from illness, and so on). It was the same from as far back as in Kemet. Today, as far removed from Kemet in place and time as Guyana, Africans who remain true to this part of their traditions still hold a ceremony and feast of thanksgiving to mark such an important landmark in the life of a person or a community, and it is called a Come True or simply a Service or a Thanksgiving, which are terms for the same activity that is widespread in the Caribbean and the Americas, where the synonymous term bembé is employed in Santeriá.

The recognition and acknowledgement of our Ancestors, the divinities and The Supreme One, as well as our connection with them, is always a very special occasion for Africans. It is not therefore necessary to have a special earthly occasion for one to pour libation. So individuals and groups may pour libation at any time they have the urge to do so. A particular libation may be addressed to any divinity or Ancestor to whom the person or group feels close or perceives the need to contact and propitiate.

The compulsion to live in harmony with the environment is a principle of African existence that arises from the even more fundamental principle of the oneness of the beings and things in the cosmos and the importance of maintaining Maat. This principle expresses itself in values, attitudes and behaviours of Africans and is often expressed through institutions. Examples include names and naming, where from time immemorial, Africans have been named for qualities admired and or respected in other animals. It may also be observed in a system of totems and taboos leading to a natural and comprehensive form of species protection, without fences, that spread itself across the land. These aspects of African culture share the same roots in the African world view as libation.

CONCLUSION

White Supremacy does not care about marching and meeting Libation is a ritual practiced throughout the African world. It is a drink offering to every category of beings and things in the cosmos, though every category may not be addressed in every libation statement. Libation is founded upon the oneness of the universe and the relation and interdependence of all beings and things therein. Its function is to maintain Maat: the harmony, balance and unity of the cosmos through maintaining the optimum relations among the various beings and things, preventing any of these relations from being impaired, or nullifying the threat of such impairment.

White Supremacy does not care about marching and meeting Libation is a ritual practiced throughout the African world. It is a drink offering to every category of beings and things in the cosmos, though every category may not be addressed in every libation statement. Libation is founded upon the oneness of the universe and the relation and interdependence of all beings and things therein. Its function is to maintain Maat: the harmony, balance and unity of the cosmos through maintaining the optimum relations among the various beings and things, preventing any of these relations from being impaired, or nullifying the threat of such impairment.

The significance of libation transcends the ritual itself. The distribution of this ritual throughout the African world illustrates that journey of journeys, the great migrations of African people from the birthplace of themselves and so of humanity in the Nile – Great Lakes region of Africa. They first went mainly northwards down the valley of the Nile to invent civilization and so transform themselves and humanity in Nubia, Kush and Kemet. Then they spread out from the Nile Valley in periodic migrations to populate and possess a continent, later the world, and propagate the ideas and always the practice of civilization.

It was not people alone who migrated north along the Nile Valley all those millennia ago, or who migrated out of the valley to populate Africa much later. Nor was it culture alone that arrived, bereft of its human agents, in all those places that were and have since become the African world. The truth is that both people and culture have made this immensely long journey, for when a people migrate, or are made to migrate, they do not leave their culture behind. That is not possible, for culture is a defining characteristic of a people and inseparable from its agents. The presence of libation throughout the African experience of life, within the entire time space correlation of African existence, demonstrates all this.

Libation is therefore, in the terms of Asante and Abarry, both ‘transgenerational and transcontinental’. (Asante and Abarry 1996, p.60). Since libation defines the temporal and physical boundaries of the African world, it may therefore help to define the boundaries of African Studies, the study of the African world. One definition of African literature is that “… African literature [is] an evolving body of interconnected works covering the entire recorded history of this continent, from the beginnings of writing in ancient Egypt to the latest publications of today.” (Armah, 2006, p. 19). Such a vision ought to be extended to embrace African Studies in general. This is a necessary start that is attractive because it attempts to begin at the beginning and it connects Africans to each other. However, there is likely to be debate around the status of oral records, which must be admitted, and the inclusion of Africans abroad.

Undoubtedly ancient, even in those ancient times about which we know much, this ritual has never been antiquated, not even antique, for it has constantly been updated and modernized – modified by the challenges of place and time. Further, it has remained a constant and fully functional aspect of African life. It is a marker of African identity. Since both libation and the African world view that instructs it are to be found all over the African world, libation may well point towards the possibility of cultural continuities and similarities as a secure basis of Pan Africanism, African repair and African redemption.

FURTHER READING

There is an enormous number of references to libation in the texts about Africa, ranging from ancient to modern times. But there is only one text that is devoted entirely to this very important ritual; Peter K. Sarpong’s work entitled Libation. But it is a mere fifty pages long, restricted to a focus upon one group of Africans in the contemporary era and confined to an attempt to reconcile the ancient African ritual with Catholic practice. The paucity of information on libation emphasises the urgency and importance of this work by Kimani Nehusi. The works by Armah and Karenga help to explain the wider spiritual context in which libation was practised in Kemet in ancient Africa, and is practised in the African world today. It also indicates how and why it is important that the African vision of self must incorporate the entire social history of the African world, from ancient to modern times.

REFERENCES

* (1954, 1972, pp. 146, 152, etc.), George G. M. James (1954), Cheikh Anta Diop (1974), Théophile Obenga (1992), Martin Bernal (1987) and others and illuminating the historical context of the references to libation made by Homer in the Illiad.

Tcontents

Sarpong, Rt. Rev. Dr. Peter Kwasi (1996). Libation. Accra: Anansesem Publications.

Armah, Ayi Kwei (2006) The Eloquence of the Scribes: a memoir on the sources and resources of African literature. Popenguine, Senegal: Per Ankh

Karenga, Maulana (ed., 1984) Selections from the Husia: Sacred Wisdom of Ancient Egypt. Los Angeles: Kawaida Publications.

Abarry, Abu S. (1996) “Recurrent Themes in Ga Libation (Mpai) Oratory” in M. K. Asante and A. S. Abarry, (eds.) African Intellectual Heritage: A Book of Sources. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Achebe, Chinua (1958, 1987) Things Fall Apart Heinemann

——————- (..) Arrow of God

Agyekum, Kofi (2004) “Indigenous Education in Africa: Evidence from the Akan” JCTAW Vol. I, No.2. Winter/Spring.

Armah, Ayi Kwei (2006) The Eloquence of the Scribes: a memoir on the sources and resources of African literature. Popenguine, Senegal: Per Ankh

Blackman, A. M. (1912) “The Significance of Incense and Libations in Funerary and Temple Ritual” Zeitscrift Für Agyptische Sprache und Altertmuskunde (ZÄS) Leipzig Vol. 50.

Bernal, M. (1987) Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization. Vol. I, The Fabrication of Ancient Greece 1785-1985. London: Free Association Press.

Braithwaite, Eward Kamau (1967, 1968, 1969, 1973) “Libation” in The Arrivants Oxford University Press.

Brunson, James E. (1991). Before the Unification: Predynastic Egypt. An African-centric View. DeKalb, Illinois: The Author.

Carruthers, J (1985) The Irritated Genie: An Essay on the Haitian Revolution. Chicago: The Kemetic Institute.

Clarke, Austin. (2003) The Polished Hoe Kingston Jamaica: Ian Randle

Publishers.

Denning, M, Phillips, O and Rudolph, G. (1979) Voudoun Fire: The Living Reality of Mystical Religion St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn Publications.

Diana Delia (1992) “The Refreshing Water of Osiris” JARCE, Vol. xxix

Finch, Charles (1988) “Imhotep the Physician: Archetype of the Great Man” I. van Sertima (ed.) Great Black Leaders: Ancient and Modern New Brunswick, USA: Journal of African Civilizations, Ltd.

Diop, C. A. (1974) The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality. Westport, CT: Lawrence Hill and Co.

Erman, A and Grapow, H. (1926, 1963, 1982). Wörterbuch der Aegyptischen Sprache, Vol. 5 Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

Faulkner, R. O. (1962) A Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian Oxford: Griffith Institute.

——————(trans.1969) The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts Warminster: Aris & Phillips Ltd.

—————– (trans. 1994) The Ancient Egyptian Coffin Texts. 3 Vols. Warminster: Aris & Phillips Ltd.

Flanagan, Brenda (2005) You Alone are Dancing. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

Gardiner, Alan (1988) Egyptian Grammar: Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs. 3rd Edition, revised. Oxford: Griffith Institute, Ashmoleum Museum.

Heath, Roy A. K. (1978). The Murderer London: Allison and Busby Ltd.

Herodotus (Trans. Sélincourt, 1954) The Histories. Penguin Books.

Hurston, Zora Neale. (1938, 1990). Tell My Horse: Voodoo and Life in Haiti and Jamaica. New York: Harper and Row

James, C. L. R. (1994) The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution. London: Allison and Busby.

James, George G. M. (1954) Stolen Legacy New York: Philosophical Library

Janssen, R. M. and Janssen, Jac J. (1996) Getting Old in Ancient Egypt. London: The Rubicon Press.

Jacq, Christian (Trans. J. M. Davis, 1985) Egyptian Magic Warminster: Aris & Phillips, Ltd.

Kaster, Joseph (trans. and ed.,1995) The Wisdom of Ancient Egypt: Writings from the Time of the Pharaohs. London: Michael O’Mara Books Ltd.

Karenga, Maulana (ed., 1984) Selections from the Husia: Sacred Wisdom of Ancient Egypt. Los Angeles: Kawaida Publications.

Kenyatta, Jomo. (1965) Facing Mount Kenya: The Tribal Life of the Gikuyu. New York: Vintage Books.

Lichtheim, M. (trans., ed. 1976) Ancient Egyptian Literature Volume II: The New Kingdom. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Mbiti, John (1988) African Religions and Philosophy. London: Heinemann.

Do Nacimento, Abdias. (1995). Orixás: Os Deuses Vivos da África. Rio de Janeiro: IPEAFRO.

Mayers-Johnson, Sheila (2004) “The Word as a Conduit for African Consciousness: MDW NTR Through Ebonics” JCTAW Vol. I, No.2. Winter/Spring.

Obenga, Théophile (1992) Ancient Egypt and Black Africa. London: Karnak House.

Opoku, Kofi A. (1978). West African Traditional Religion. Accra: FEP International Private Press.

Sarpong, Rt. Rev. Dr. Peter Kwasi (1996). Libation. Accra: Anansesem Publications.

Schäfer, H (1898) “Eine altägyptische Schreibersitte” ZÄS. No. 36.

Tyldesley, Joyce (ed. 2004). “The Destruction of Mankind” in Tales from Ancient Egypt. Bolton: Rutherford Press Ltd.

Williams, Bruce (1985). “The Lost Pharaohs of Nubia” in Ivan Van Sertima (ed.) Nile Valley Civilizations. New Brunswick, USA: Journal of African Civilizations, Ltd.

Wilson, J. A. (trans.1969) “Deliverance of Mankind from Destruction” in J. B. Pritchard (ed.) Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament 3rd Edition. Princeton, NJ: University of Princeton Press.

Yellin, Janice W. (1982) “Abation-style milk libation at Meroe.” N. B. Millet and A. L. Kelley (eds.) Meroitica. Proceedings of the Third International Meroetic Conference, Toronto, 1977. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.

Wilkinson, J. Gardner (1994). The Ancient Egyptians: Their Life and Customs. Vol. I. London: Senate.

Kimani Nehusi (PhD) is an expert in Ancient Egypt and this extract is from his forthcoming book by the same name.