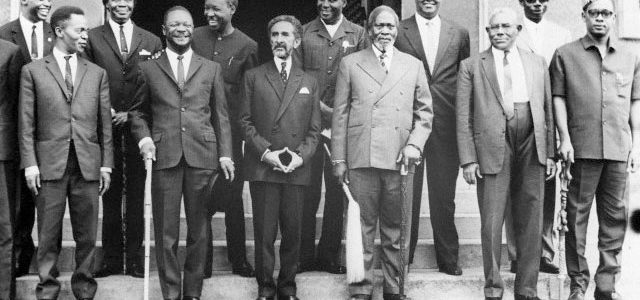

The early Pan-Africaninsts were concerned with repudiating the eurocentric and racist views that justified slavery and later European imperialism. These views, which argued that Africa and Africans had played no part in history were opposed by the leading thinkers from Africa and the Diaspora such as James Africanus Horton, E.W. Blyden, Martin Delaney and Alexander Crummell, who were thus the champions of the notion of Africans as the makers of their own history.

But their plans for African regeneration and independent development were hampered by the fact that what they advocated was usually a version of the same eurocentric approach that they were criticising, and one that took no account of the needs of the majority of the African people.

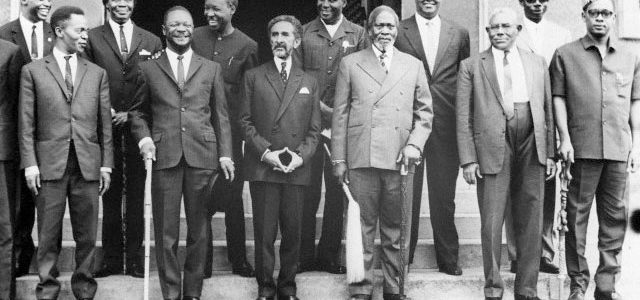

Du Bois

In response to the conquest and division of Africa by the European colonial powers the early Pan-Africanists, such as Delany, demanded “Africa for the African race and black men to rule them,” which became a rallying cry for Africans throughout the continent and the Diaspora, from the 19th century until the slogan was once again promoted by Marcus Garvey in the first and second decades of the last century. But the fact is that although during this period important networks of struggle were established between Africans in various continents neither Delany, nor Garvey or the other early Pan-Africanists devised any concrete programme to realise their demand

The first Pan-African gathering to develop such a programme was the International Conference of Negro Workers, convened under the auspices of the communist-led Red International of Labour Unions (Profintern) and the Provisional International Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers held in Hamburg, Germany in 1930. This conference clearly identified the enemy – “capitalist exploitation and imperialist oppression” and it was also the first Pan-African gathering to fully concern itself with the rights of the majority of the African population, to view the workers and farmers as their own liberators alongside the working people of all countries. It was also the first Pan-African event to raise the demand for the “immediate evacuation of the imperialists from all colonies”, and for “complete national independence and right of self-determination.” It was also the first such gathering to include delegates from workers and farmers organisations in Africa, as well as the countries of the Caribbean and the US..

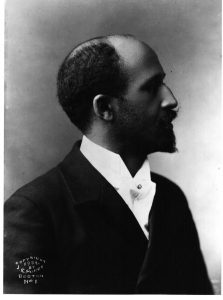

George Padmore

Between 1930 and 1945, the ideology of Pan-Africanism went through something of a transformation, largely as a consequence of the work of Africans and those of African descent residing in Britain, or linked to those in Britain by the important networks that were developed throughout the Pan-African world. These drew together activists like George Padmore and Isaac Wallace-Johnson, who had both participated in the Hamburg conference. The networks linked together anti-colonial and anti-imperialist organisation in Africa and those in Europe and America, in which Africans from the Diaspora often played a leading role, such as the US-based Council on African Affairs, led by Paul Robeson and Alphaeus Hunton. An increasingly Marxist-influenced Pan-Africanism developed – informed and influenced by such individuals as Padmore, and by what were generally agreed to be major advances in economic, political and social developments in the Soviet Union. A more militant approach to anti-colonialism in Africa was also brought about as a consequence of the wide-scale effects of the Depression, the fascist invasion of Italy, the agricultural boycotts in West Africa, the labour rebellions in the Caribbean. Gradually Pan-Africanism developed into a movement and ideology concerned with the masses of the people and with a particular emphasis on the future liberation of African from colonial rule. It was this form of Pan-Africanism that came to the fore in 1945.

The 1945 Pan-African Congress, held in Manchester, England, and viewed by many as a key moment in the anti-colonial struggle, was largely organised by George Padmore and the Pan-African Federation in Britain. This was the first such congress in which most of the delegates represented organisations of workers and farmers, the vast majority in the African colonies. This Congress rejected the territorial boundaries and indeed the whole notion of the nation-state imposed on Africa by the colonial powers. It rejected eurocentrism in a much broader way than had hitherto been the case, and included a condemnation of imposed foreign political systems and the role of the market in economic affairs. It placed some emphasis on the needs of the masses of the people and highlighted the need to base the anti-colonial struggle on the majority, the workers and farmers as well as other sections of the population. It also saw the anti-colonial struggle in Africa as part of a much wider struggle which included the struggles of all those of African descent and all those in the colonies for emancipation, but which also included the struggle or aspirations of the majority of working people at that time for empowerment and a better world.

The Pan-Africanisn that has developed in the last 60 years has been informed by the work of many key thinkers and activists: Fanon, Cabral, Rodney, Malcolm X and others. But what advances have been made? Two further Pan-African Congresses have been held, and most recently the Africa Union has been established in which Africans of the Diaspora have been accorded a key role.

Without commerce and industry, a people perish economically. The Negro is perishing because he has no economic system–Marcus Garvey

Most African and Caribbean countries have gained formal independence and yet are still not liberated and their populations remain impoverished and dis-empowered. Yet again, under the guise of the “white man’s burden,” the “civilizing mission” and the imposition of eurocentric values, Africa is being drained of its resources, material and human, devastated, and re-divided by the big powers. The African Diaspora in Europe, North America and elsewhere, as recent events in New Orleans and France have graphically demonstrated, also face poverty, racism and disempowerment.

Over a century ago Africanus Horton spoke of the need for Africans to develop a “true political science” but can we say that such a science has been developed? What is the political philosophy that can guide Africa and Diaspora liberation to genuine liberation and empowerment? Surely it is now time to analyse and re-evaluate over a century of Pan-Africanism. There is a need to analyse the experience of over a century of struggle in Africa and throughout the world. We have to sum up the experience gained from Libya as well as South Africa, that of Haiti as well as Cuba, that of Britain as well the US. Basing ourselves on understanding our own experience, as well as the experience of others, will enable us to develop a politics of liberation for the 21st century.

Dr Hakim Adi (Ph.D SOAS, London University) is Reader in the History of Africa and the African Diaspora at Middlesex University, London, UK. Hakim is the author of West Africans in Britain 1900-60: Nationalism, Pan-Africanism and Communism (Lawrence and Wishart, 1998) and (with M. Sherwood) The 1945 Manchester Pan-African Congress Revisited (New Beacon, 1995) and Pan-African History: Political Figures from Africa and the Diaspora since 1787 (Routledge, 2003). He has appeared in several television documentaries and has written many articles on the history of the African Diaspora and Africans in Britain, including three history books for children.

No comments so far.

Be first to leave comment below.